The all-star team of government officials, scientists and industry executives who tackled COVID-19 made great strides in the development of an effective vaccine against the novel virus, but that is no guarantee that the United States will be ready for the next pandemic that rears its head, speakers at a MITRE webinar on biopreparedness said.

Waning public and political interest, changing personnel, and competing priorities are already sapping the institutional knowledge that drove Operation Warp Speed to deploy the current trio of vaccines, which the panelists said made it critical that steps be taken sooner rather than later to reinforce the playbook that public-private teams will use to address not only public health emergencies but other types of national crises as well.

“There is no limitation to the possibility of us having to do this over again and over again,” said Robert Kadlec, senior counsel on the U.S. Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee and former Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “These partnerships can’t just start when the crisis happens; it’s really about building long-term relationships.”

While Operation Warp Speed was launched by the Trump White House, the roots of the effort went back to previous administrations’ responses to lower profile epidemics that threatened the United States, such as the 2013-2016 Ebola virus and the H1N1 swine flu in 2009. Those responses and procedures gave the Warp Speed team at least a starting point for pulling together resources and expertise and drafting an execution strategy when time was not in their favor.

“In May 2020, many people said, ‘You can’t develop a vaccine that quickly,’ and we did it,” said Dr. Matt Hepburn, who at the time was the head of vaccine development for Operation Warp Speed and remains Director of COVID Vaccine Development for the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

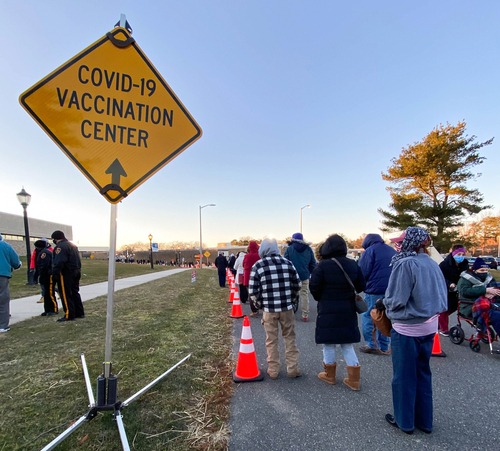

The 2020 skepticism was not unwarranted as observers pointed to the long timelines required to get a new vaccine from the bench, through the FDA approval process, and then manufactured, packaged and shipped at the scale needed to basically give everyone in the country, if not the world, a shot. Along with the pure science end of the project, Warp Speed also forged new levels of cooperation in handling a myriad of moving parts to get the vaccine to street level.

“Our charge now is to make sure we don’t regress,” Hepburn said.

Operation Warp Speed was praised by the speakers at the Oct. 14 online event as much for its level of cooperation as it was for the actual delivery of the COVID-19 vaccines. Despite the high level of attention from the media, Wall Street and elected officials at all levels, a cadre of experts from a wide range of disciplines was able to put together a battle plan that satisfied the business and public-health requirements of turning the tide against the frightening pandemic.

“We have learned a lot, for example, about the nuts and bolts of contracting and funding,” said Hepburn. “We have shown that we can move fast.”

The key is not forgetting those basics as time goes on and COVID-19 fades. The speakers all considered a model that brings as many partners as necessary to the table in an atmosphere of mutual trust as the best approach to not only meet unknown future threats, but also current situations, including climate change, cybersecurity and the squeeze on semiconductor chips.

“What’s striking is that we have a success, which is Operation Warp Speed,” said Richard Danzig, a former secretary of the Navy and currently senior advisor at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. “But that phenomenon of bringing people in from the private sector to government is extremely rare.”

Danzig and other speakers contended that an overall closer relationship between industry and government agencies would require changes in the attitude over conflicts of interest, protection of intellectual property, contracting and funding approvals, and professional development to raise the expertise among bureaucrats and other officials.

“In general, it is how we build cooperation,” Danzig said. “We need to think of government-private sector cooperation in generic terms.”

“It really means respecting the different skills around the table and leveraging them,” said Phyliss Arthur, vice president of Infectious Disease & Emerging Science Policy for the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO). “The government really owns the strategy, but a lot of the expertise on implementing that strategy rests with the private sector.”

In the high-pressure fishbowl of Washington, it could be easy for individual members of the team to become more concerned with their own turf and own interests. That, however, would be a fatal mistake. Kadlec summed up the bottom line for the next Operation Warp Speed team to build trust among a diverse group: “We can’t screw our partners, big or small.”