Legislators are not waiting for the coronavirus pandemic to subside to suggest ways to combat future health emergencies.

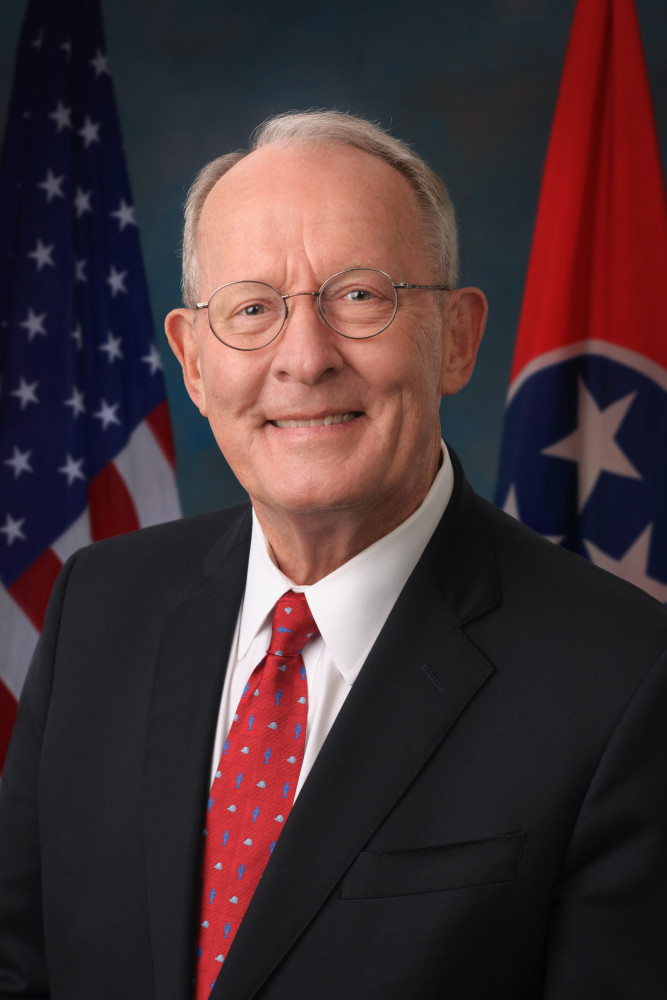

In his recently released white paper “Preparing for the Next Pandemic,” U.S. Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-TN) outlines five recommendations Congress can act on in the next six months to prevent the mistakes of this pandemic and other health crises the United States has experienced in the last 20 years.

The recommendations include:

* Tests, Treatments, and Vaccines – Accelerate Research and Development

* Disease Surveillance – Expand Ability to Detect, Identify, Model, and Track Emerging Infectious Diseases

* Stockpiles, Distribution, and Surges – Rebuild and Maintain Federal and State Stockpiles and Improve Medical Supply Surge Capacity and Distribution

* Public Health Capabilities – Improve State and Local Capacity to Respond

* Who Is on the Flagpole? – Improve Coordination of Federal Agencies During a Public Health Emergency

“Even the experts underestimated the ease of transmission and the ability of this novel coronavirus to spread without symptoms,” Alexander said. “We continue to learn more about the science and trajectory of this disease that is changing the response on a daily basis. In the midst of responding to COVID-19, the United States Congress should take stock now of what parts of the local, state, and federal response worked, what could work better and how, and be prepared to pass legislation this year to better prepare for the next pandemic, which will surely come.”

Alexander, who is chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, added that COVID-19 has exposed gaps not previously identified in the health systems, including unanticipated shortages of testing supplies and sedative drugs, which are necessary along with ventilators for COVID-19 patients.

These gaps have existed for two decades, Alexander writes, as the Government Accountability Office, private sector experts, and multiple presidential administrations have repeatedly warned that the federal government is not completely equipped to handle a significant public health threat. In that time, states may have improved disease surveillance and communication systems and laboratory capacity, but regional planning between states is lacking. States’ surge capacity— being able to evaluate, diagnose, and treat large numbers of people – is also strained as evidenced by COVID-19. When it comes to receiving and distributing medical supplies and items for mass vaccination from the Strategic National Stockpile, many states have not finalized their plans.

In an exercise led by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) last year, the scenario envisioned a highly transmissible strain of H7N9 avian influenza detected in a tour group that recently traveled to China. The report from that exercise showed that HHS did not have the mechanisms in place to direct other departments and agencies during a nationwide response without the support of FEMA. HHS did not have sufficient funding to respond to a national crisis without supplemental appropriations from Congress. The scenario also demonstrated that the international supply chain for necessary medical supplies would not meet the global demand during a pandemic.

Being able to contact trace is critical for health professionals to mitigate disease spread. But it was not until February that HHS published an interim final rule allowing contact information on passengers and crews from abroad to be collected. Among Alexander’s recommendations is that the Departments of Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and Transportation coordinate to improve access to passenger contact information by appropriate public health officials to better inform responses to infectious diseases.

Alexander also encourages manufacturers of medical countermeasures to make their products in the United States, a challenging task when current facilities can only be used to manufacture biological products and not small molecule drugs. He recommends Congress and the administration identify and implement public-private manufacturing models to “improve and maintain sustainable domestic vaccine manufacturing capacity and capabilities.”

The distribution of medical countermeasures can be as important as making them. When the FDA issued an emergency use authorization for remdesivir, Gilead Sciences, the drug’s manufacturer, donated 607,000 vials of the drug to HHS to distribute nationwide. However, the initial shipments were delayed. State and healthcare facility officials were confused regarding the distribution strategy and when they would receive remdesivir. Alexander writes that plans should be established in advance for how the federal government, states, and the private sector will coordinate to determine the distribution of new tests, treatments, and vaccines.