Former members of U.S. Customs and Border Protection downplayed the idea that a wall alone would be enough to strengthen the U.S. southern border in a Senate hearing on Tuesday, framing it as part of a broader strategy.

Speaking at a Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs committee hearing on fencing along the southwest border, ranking member U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-MO) raised concerns about how much the wall will cost, how difficult it will be to acquire the land for the wall, and some of the impacts on American landowners on the border.

“There is no one in America that doesn’t want our borders secured,” McCaskill said in her opening statements. “But I’ve not met anyone that says the most effective way is to build a wall across the entirety of our southern border. The only one who keeps talking about that is President Trump.”

Lawmakers and witnesses said there is no one solution to secure the border.

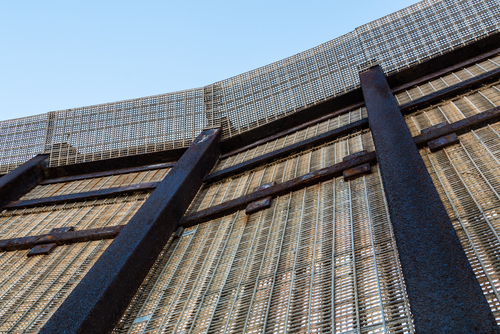

“We need a layered approach to border security, one that includes technology, manpower, a commitment to the rule of law, and the elimination of incentives for illegal immigration,” said U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI), chairman of the committee. “But it should also be obvious, as the Obama administration’s chief of the U.S. Border Patrol testified before the committee, that fencing does work and we need more of it.”

While both the witnesses testifying before the committee and the committee itself was open to a variety of methods going forward, no easy — or cheap — solutions to secure the border could be agreed upon. Testimony made clear, however, that border security demands an intrinsic web of activity, wherein each strand strengthens the whole operation.

“The links in the chain have to be equally strong,” said Ronald Colburn, former deputy chief of the U.S. Border Patrol at U.S. Customs and Border Protections, part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Together with David Aguilar, a former acting commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Colburn laid out the hard truths of the border: that it has changed significantly in terms of identity and problems since he started out there 30 years ago, that the criminals who make use of it are constantly adjusting their tactics, and that the United States, therefore, must also adapt.

Roads for border control access, levies, fencing, technology such as drones and mobile observation towers, concrete immigration policy and an increase of personnel were all discussed as ways to combat criminal activities — described as possessing amazing infrastructure by Colburn — along the sprawling southern border with Mexico.

“We’d go a lot further if we simply acknowledged there’s a lot of other ways to secure the border than just building a wall,” U.S. Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND) said in an exchange with Johnson.

Even in supporting increased efforts along the multitude of states across which the border sprawls, Aguilar said that investing millions in a wall — or fence — will not immediately stop crime. That the purpose of a wall is, in fact, not to stop crime, but to slow it.

“We cannot forget the purpose of the fence is to deter, impede, to create more time and distance for officers to react and take the actions necessary,” Aguilar said.

The sole witness from the private and academic side of the issue came in the form of Terence M. Garrett, professor and chair of the public affairs and security studies department at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. He said past government contracts for border fencing have benefitted corporations, not private owners and pointed to south Texas sentiment about the wall — chiefly, fears that it will cost potentially millions as the result of a trade war with the United States’ southern neighbor.

It was also in a discussion between McCaskill and Garrett that the specter of eminent domain was brought up. After pointing out that roughly two-thirds of the Mexican border rests on private and state-owned land, McCaskill asked, if the government was likely to run into resistance if it took more land from Texas property owners.

“They have the resources to fight,” Garrett said. “There are other places along the border that previously did not get the wall. We’re talking about hundreds more miles. And they’re all entitled to a jury trial.”

This also sparked an apparent rebuke from Aguilar, who said that while eminent domain cases were heartbreaking, the oaths that people like Colburn and he — members of the border security community — took were to the people of the United States, not Texas, or any individual state.

A mix of infrastructure, technology and personnel seemed to be the focus of efforts going forward. Colburn painted a portrait of how the border has changed over the years, from hand-dug fencing to combat “mom and pop” smugglers, to government organized efforts in the wake of 9/11, to combat mass, cartel-organized border crossings.

“Crime will never go away and they won’t stop trying, but we can create deterrents,” Colburn said.