A pair of studies conducted by scientists from the United States, United Kingdom, Thailand, Bangladesh, Namibia and Norway suggest that combining data of parasite genetics and human movement could improve efforts at tracking and fighting malaria transmission.

“Countries and regional blocs are working to identify where parasite importations are common and to pinpoint the sources of imported cases to develop more effective and targeted malaria interventions,” said Sofonias Tessema, a postdoctoral scholar at University of California-San Francisco, and co-first author of one of the studies. “But routinely collected data, such as malaria case counts obtained from health facilities, may not provide much information on importations. Malaria cases are often classified as either having been infected locally or imported based on the patient’s self-report of recent travel. With only travel history data, it can be difficult to assess accurately whether malaria parasites were acquired locally or during travel.”

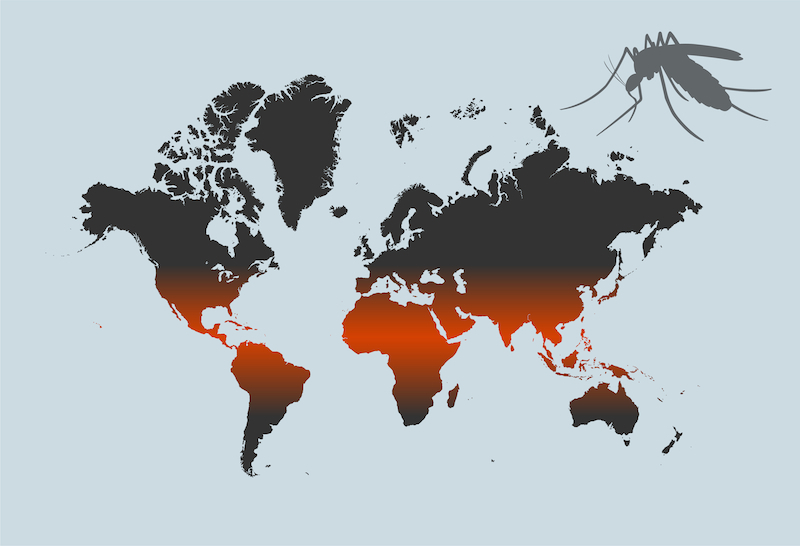

Having access to more detailed information could allow malaria control programs to strengthen their efforts at control, Tessema and their colleagues conclude. Malaria has been in decline among countries. However, its transmission varies, posing a consistent cross-border threat.

For their studies, scientists used two different methods in two distinct locales. The first, in Southern Africa, focused on parasite genetic data to estimate the contribution of importation, then compared it with human movement data. They were then able to narrow down relevant sources of malaria parasites in the region, ashtye realized that cases from nearby were more likely to be closely related genetically. That genetic data also let them identify more evidence of parasite connectivity over hundreds of miles than from other data sources, suggesting local efforts and regional coordination could be improved.

The second study focused on Bangladesh, through measurement of the spatial spread of malaria parasites in the region. In so doing, they discovered that frequent mixing occurs in low-transmission areas in the southwest of the Chittagong Hill Tracts region, suggesting that interventions will be necessary to eliminate the disease and reduce its import capabilities.

“Unlike risk maps generated from clinical case counts alone, our method also distinguished areas of frequent importation as well as high transmission,” said Richard Maude, head of Epidemiology at Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU), and a co-senior author of this study.

The findings of both studies were published in eLife.