North Korea’s threats to carry out a nuclear strike on the United States underscores the need for the medical community to be prepared to treat potentially large numbers of patients contaminated by radiation in the event of an attack, but new research shows more training is needed among emergency medical personnel.

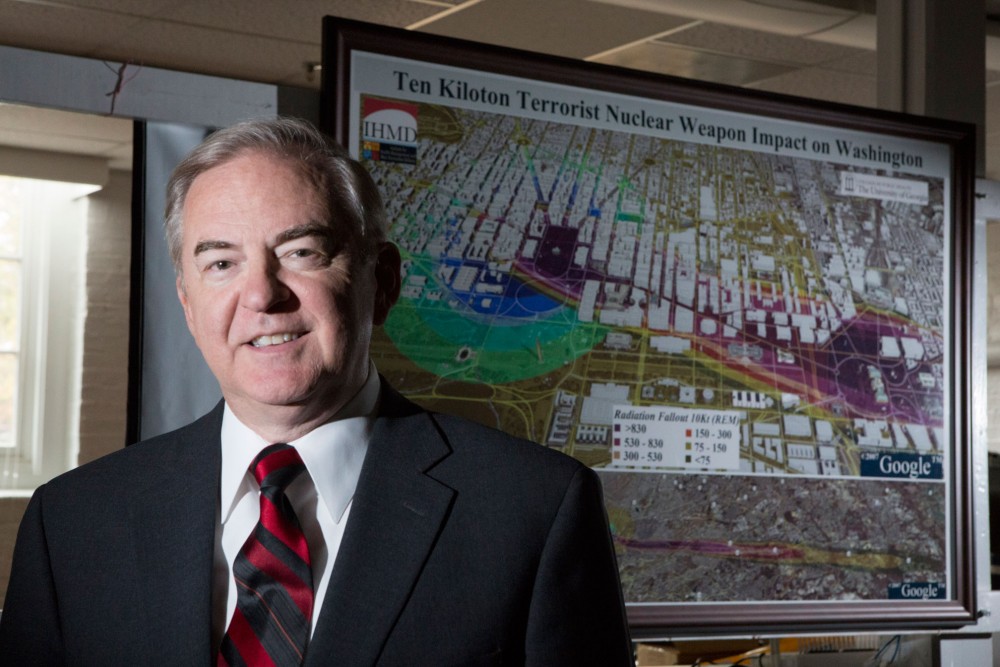

A survey of 418 U.S. and Japanese medical professionals found they lacked knowledge regarding nuclear and radiological contamination risks, which can affect their willingness and ability to respond to those types of disasters, according to Cham Dallas, a professor in the department of health policy and management at the University of Georgia and director of the Institute for Disaster Management in the College of Public Health.

Dallas and his colleagues recently published the report, “Readiness for Radiological and Nuclear Events among Emergency Medical Personnel,” in Frontiers for Public Health.

Experts have expressed concern over terrorism involving radioactive materials as a likely threat to the United States, and point to the potential for radiological materials to be released in the aftermath of nuclear reactor accidents such as Fukushima in 2011 and Chernobyl in 1986. Those threats highlight the importance of expertise and training for emergency medical responders.

But given the lack of nuclear warfare and the rare occurrence of radioactive materials being released into the environment, high-level expertise remains in very few military or civilian sectors, according to the report.

“This is especially evident in the field of medicine, where radiation expertise is almost exclusively related to training and proactive with therapeutic regimens, under tightly controlled conditions, but for large scale exposures or contamination is not well understood or taught,” the report said.

When medical professionals buy into myths surrounding radioactivity, it can affect their willingness to respond to a nuclear disaster, and it can also impact their ability to effectively treat patients, Dallas said.

“How many emergency people have been injured treating a radioactive patient? The answer is zero,” Dallas told Homeland Preparedness News in an interview. However, in the study, when medical professionals were asked which disaster type would make them unwilling to come to work, “nuclear bomb” topped the list.

“Studies have shown that for a biological outbreak, as seen with SARS, medical personnel would come to work and provide medical care if they felt safe,” the report said. “However, for a radiological incident, as seen in the aftermath of Fukushima, there are indications that medical personnel might have an unwillingness to respond to unusual emergency conditions with which they are not familiar, and consider dangerous.”

Dallas said most portrayals of nuclear attacks and the effects of radiation in Hollywood movies or on television are not accurate, and that fuels misunderstanding among the general public and the medical community.

“To be clear, radiation is bad, but for example, one of the big myths – and we discovered this at Chernobyl – is that radiation causes birth defects,” Dallas said.

Many patients are wary of getting an X-ray because they are concerned about radiation exposure. In fact, women are warned to notify their health care providers if they’re pregnant. Indeed, radiation can harm fetuses and cause birth defects, Dallas noted. In a hospital, the radiation source is just a few feet away, and an X-ray of the torso of a pregnant woman is more likely to result in close-range exposure to the fetus.

But radiation exposure from X-rays is different from environmental radioactivity. “When radiation is falling from the sky, the source is far away; the intensity falls off …,” Dallas said, adding that when radiation is distributed it significantly decreases its level of intensity.

The Chernobyl nuclear disaster exposed roughly 90,000 women to radiation. “At least 30,000 women terminated their pregnancies due to radiation fears, while 60,000 women carried to full term,” Dallas noted. The babies of women who carried to full term did not experience any problems, he said. “There was no difference between exposed and unexposed pregnant women,” said Dallas, who received permission to visit the Chernobyl area in 1989.

Additional lessons can be drawn from Chernobyl.

For example, 8,000 to 10,000 children developed thyroid cancer after the Chernobyl distaster, according to Dallas. “They received potassium iodide, which protects the thyroid from irradiation, but it was received too late.” DTPA (Diethylenetriamine pentaacetate) also protects the body from radioactive plutonium, but if it isn’t received within 24 hours, it’s less effective.

The problem of emergency preparedness also is being compounded by the declining number of trained medical personnel.

“Despite the acknowledgment by experts that a radiological or nuclear incident is inevitable, the health care community is not comfortable, knowledgeable, or prepared to deal with the contaminated or exposed patient,” the report concluded. “More research as to what needs to be taught resulting in meaningful training needs to be developed.”